The Neurological Side of Positive Affirmations

Positive affirmations have been used, in various forms, for thousands of years. Affirmations are phrases that you can repeat to yourself over and over, locking

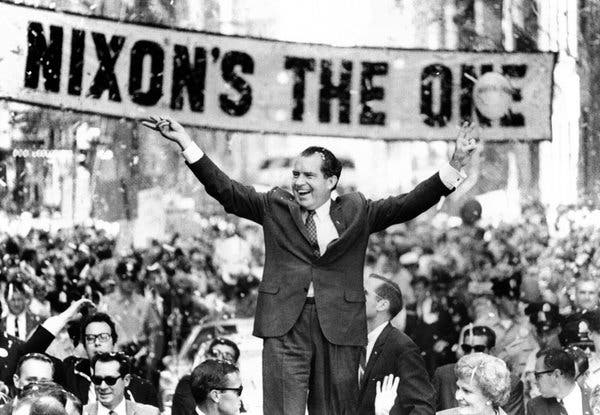

In June 1971, US President Nixon officially declared a “War on Drugs,” stating that drug abuse was the public enemy number one. The year in which Nixon first announced the fight against drugs worldwide, two congressmen published an investigation into the growing use of heroin among American soldiers. This investigation shows that 10 – 15% of the troops were addicted to heroin. An increase in recreational drug use in the 1960s and research into the use of Heroin by American soldiers was the starting signal for the War on Drugs for the Nixon government.

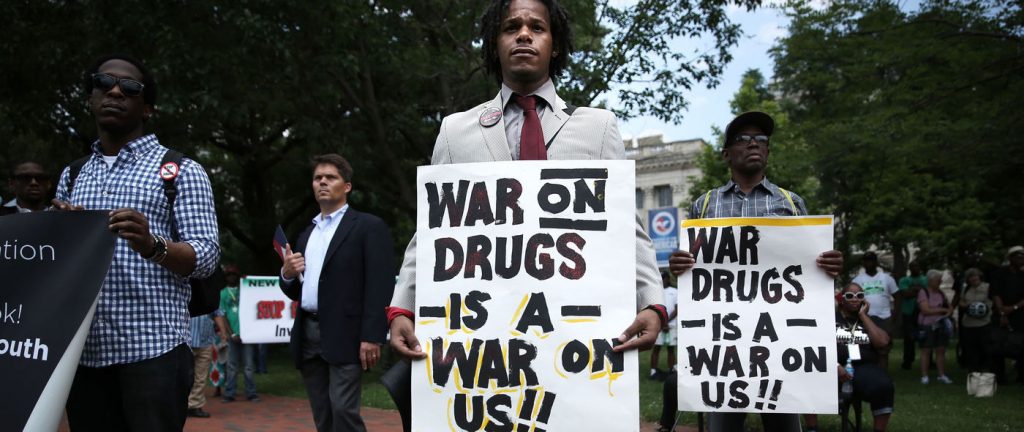

“You want to know what this was really all about? The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. Do you understand what I’m saying?” – John Ehrlichman, Nixon’s former domestic policy advisor

The start of the “lock-up and throw away the key” approach to drug crime, currently still in force in the United States, came into existence in 1973 during the Nixon White House. The strictest drug legislation in American history passed under New York governor Nelson Rockefeller. The Rockefeller drug laws include mandatory minimum penalties for possession of drugs and made it impossible for judges to be flexible in some instances where this might make sense. These laws later became the model for President Reagan’s significant escalation of the War on Drugs in the 1980s

George H.W. Bush, former vice president, began to advocate the deployment of the CIA and the US military. The Office of National Drug Policy established in 1988, which forced a national media campaign against drug use among young people. The then presidents supported these campaign activities during the 1990s and early 21st century, and this policy is still in force.

“Drug abuse is the public enemy number one” – Former President of the United Nations Richard Nixon (1969 – 1974)

It is often said that Richard Nixon started the War on Drugs. He came up with the term, established the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) – and President Ronald Reagan escalated the war, but the real War on Drugs began much earlier.

The United Nations War on Drugs Conventions of 1960 and 1971 may have caused the greatest ban on research in the field of medical- microdosing and life sciences. Think of treatments for brain diseases that have been interrupted for years. The discovery of new psychiatric medication, whether it is for the treatment of depression, autism or schizophrenia, has almost stopped — for example, the antidepressants currently on the market date back to 1950. During the 1960s, more than 1,000 scientific publications reported how LSD could be a tool to make psychotherapy more effective. MDMA was even used in the 1970s as an adjunct to talk therapy.

Many of these “illegal” substances have medicinal purposes — for example, opiates for pain, amphetamines for narcolepsy and hyperactivity disorders, and anaesthesia during surgery. These drugs are “illegal”, which means that penalties impose when you offer or possess these substances for sale. Some of these penalties can be very serious. In some countries, this means getting the death penalty for personal possession.

Many traditional medicines include plant sources. Among other things, cannabis is a medicine for over 4,000 years for diseases such as malaria and rheumatism. Since the war on drugs, major restrictions have been imposed on this. These limitations mean that research into the medical use of cannabis and other substances has hardly taken place in the past 50 years.

The drug war that we know started much earlier in the 1870s. The ban on opium, cocaine and marijuana and other dissociative and psychedelic substances appear to have links with both racism and xenophobia.

Midway through the 19th century the west coast of the United States had an influx of Chinese immigrants. The government started an aggressive racist propaganda attack against cocaine-using black Americans and opium users called “The China Men”. American Citizens thought Chinese men were luring women to opium holes to take advantage of them. Hysterical media stories claimed that white women who used these drugs ran away with men of different races. Propaganda did not stop there. Newspapers, including the New York Times, often pressed inflammatory headlines to play crimes committed by black men who used cocaine.

Private recordings of Nixon from his time as president reveal disturbing statements about how he thought about drugs and the people who used them. The real revelation came to light during an interview 26 years ago with Nixon’s former top adviser John Ehrlichman, just recently published in Harper’s Magazine.

“We created the war on drugs to “criminalize” black people and the anti-war left. We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin. And then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course, we did.” – John Ehrlichman, Nixon’s former domestic policy adviser during the interview in 1994 with Dan Baum.

In 1977, Jimmy Carter became president in which the United States experienced a slight interruption of the war on drugs, and eleven states decriminalized possession of marijuana. During his first year in office, the Senate Committee voted to decriminalize one ounce of marijuana. In the 1980s, the interruption of the War on Drugs came to an end. New President Ronald Reagan radically strengthened and expanded Nixon’s War on Drugs policy. In 1984, his wife Nancy Reagan launched the “Just Say No” campaign to educate children about the dangers of drug use. President Reagan’s reorientation of drugs led to a significant increase in detention for non-violent drug offences.

Critics also pointed to data showing that people of colour were the target and were arrested on suspicion of drug use at higher speeds than whites, leading to disproportionate detention among colour communities.

More than half of Americans currently in prison are drug offences. Of the approximately 2 million people behind bars in the US, around 500,000 are convict for drug offences. That is more than the total number of people imprisoned for all crimes in Western Europe, although the US has 100 million fewer people. In 2009, 1.66 million Americans were arrested on charges of drugs. Before Reagan allowed the drug war to escalate ultimately, 150 Americans out of 100,000 were in prison. That figure is now around 707 out of 100,000 Americans.

Whether America wins the war on drugs successfully or loses, it heavily depends on who you ask. The conviction of American youngsters for violating the Opium Act almost always means that they cannot follow education for a short or more extended period and lose their voting rights and opportunities on the labour market. Therefore, some believe that the War on Drugs resulted in the creation of a permanent underclass of citizens who have few educational and employment opportunities, often as a result of the drug crime penalties which in themselves are the result of attempts to earn an income through the lack of educational or employment opportunities.

The recent legalization of marijuana in various states and the District of Columbia has led to a more tolerant political view of recreational drug use. Many countries, such as Portugal, have decriminalized drugs and are starting to focus on drug rehabilitation. Countries such as the Netherlands have even legalized the recreational use of cannabis.

Many Western countries attempt to exempt the medical use of prohibited substances from the laws which try to limit any kind of drug use. In the UK and the US, drugs such as morphine and amphetamine are now exempt. In practice, this means that they are available at pharmacies, and most universities can use them for research purposes.

Public support for the war on drugs has declined in recent decades. Some believe that the campaign has not been effective or has led to racial differences. However, others still passionately support the effort. Technically, the War on Drugs is still being fought, but with less intensity and propaganda than in the early years.

The decades-long research hiatus has taken its toll. Psychologists would like to know whether MDMA can help with intractable post-traumatic stress disorder. Whether LSD or psilocybin can provide relief for cluster headaches or obsessive-compulsive disorder, and whether the particular docking receptors on brain cells that many psychedelics latch onto are critical sites for regulating conscious states that go awry in schizophrenia and depression. If some obstacles to research can be overcome, it may be possible to finally detach research on such as psychoactive chemicals from the hyperbolic rhetoric that is a legacy of the war on drugs. The endless obstructions have resulted in an almost complete halt in research to drugs. As the world works towards lifting the ban on pharmacological innovation and research, it’s essential to encourage and support the efforts of scientists.

Positive affirmations have been used, in various forms, for thousands of years. Affirmations are phrases that you can repeat to yourself over and over, locking

Lion’s Mane Mushroom is an all-natural species of fungi that has been in use for centuries to help people improve their health and

Microdosing and Silicon Valley? Those unfamiliar with microdosing may find that the term conjures up images of mushroom-munching hippies with long hair. However, microdosing has

Have you been microdosing for a while and would like to take things to the next level? When travelling down the microdosing rabbit hole, you

Lions mane mushroom: perhaps one of the most beloved medicinal mushrooms. The word of these powerful little fluff balls has been circulating the

If you are reading this, then welcome to the microdosing rabbit hole! When it comes to this practice, the benefits are endless. Microdosing may

GET 10% DISCOUNT WITH NOTIFIED ABOUT THE LATEST NEWS AND UPDATES. NO SPAM, WE PROMISE!

FREE Tracked shipping on orders over €250 to EU countries.

Monday- Friday 8.30am- 5pm (CET)

A range of options available

Guaranteed delivery or your money back